There's an old children's game that involves holding a makeup mirror under your nose and walking around the house with it held there, facing up towards the ceiling. The mirror reflects the ceiling into your peripheral vision, and you start to subconsciously navigate around the house as if the ceiling were the floor - stepping over the tall thresholds created when door headers are reflected onto the floor, and running into furniture that goes unseen on the smooth expanses of the ceiling. This trick and others like it have always been of interest to me. I suppose I was destined to experiment with drugs as some of my earliest pastimes were spinning around until I was dizzy, holding my breath, and pushing on the outsides of my eyeballs until I saw double. But as a hard-core rationalist and someone who permanently gave up psychedelics after a single, life-changing experience at the tender age of seventeen, I've always been drawn to the types of out-of-body experiences that can be attributed to glitches in our own internal processing or other types of visual and auditory phenomena that have a simple, rational explanation.

As a kid, I had a treasured book that dealt with metaphysical phenomena such as astral projection and lucid dreaming. The astral projection bit always seemed a bit hokey to me, but I still applied the techniques and tried to imagine myself pinned against the bedroom ceiling, staring down at my own prepubescent body, comfortably wrapped in my favorite brown and orange 70's sheets with the mountain/sunset motif. I had more success with lucid dreaming, and I still have some successes finding the cracks in the veneer of a dream's believability - those cracks that are the openings allowing you to step in and take control of the dream for yourself.

This interest in the ability to exert a level of control over what is essentially a delusion takes me back to my problem with psychedelics. If you take enough acid (which I certainly did that one night), you can reach a point where you can no longer continue to tell yourself that you feel the way you feel because you ingested a foreign substance. It's the opposite of lucid dreaming. Once you lose the thread that ties you back to reality ("I did drugs, and this will pass"), your current situation becomes your reality - and your reality is theonly reality. Our only connection to "reality" is through the unreliable input from our senses and we all experience the world in our own ways. There is no objective reality.

When I awoke from my one-and-done acid trip with my seventeen-year-old body tied down to a hospital gurney, the doctors who insisted that I stay there for three days against my will did so because they were ostensibly concerned that I might have a "flashback". It didn't help my state of mind any that the reality I had woken up to was just as surreal as the drug-induced one that I had just left behind. Neither did the fact that they pumped me full of other psychoactive medications - drugs which caused me to shake violently - and then proceeded to interrogate me about why I was shaking. Laying there supine, naked, struggling against the thick leather restraints, I did my best to astral project myself right out of that hospital room, but alas, it wasn't going to happen.

I'm pretty sure my elite team of doctors got their training from watching old episodes of Dragnet, still, as the years have gone by, the dreaded flashbacks they were so valiantly shielding me from (with Haldol and stomach pumps) never came to pass in the sense that I never had the experience of unexpectedly returning to my previously-drugged state, but I did eventually experience a type of flashback, one that manifested itself as a reliving of past traumas experienced during my experience on acid - little flashes of PTSD. Just because something didn't really happen doesn't mean that it didn't happen for you. I still have nightmares about my seventeen-year-old nightmares.

Perhaps because of the memories of these past traumas, I've become interested in creating environments and experiences now that shift our perceptions as a sheer exploration of joy. I want to induce auditory and visual hallucinations that can be turned off at any point - take off the headphones or step out of the room and it's over. The ability to escape these situations does not make them any less powerful, it simply makes them safer and less likely to traumatize the participants. Still, these experiences have the potential to show us what's on the other side of the curtain, not that there is a world of magic and mysticism out there, but that the world is simply what we make of it. So maybe there is magic and mysticism after all. There is if you want it. I don't really, but anything is possible.

Reading in bed without craning your neck is possible if you have a pair of these fancy new "Lazy Reader" prismatic eyeglasses! The glasses shift your gaze 90 degrees to the south, so when you're lying in bed staring at the ceiling wishing that the Haldol would wear off and somebody would give you a blanket -instead of actually staring at the ceiling, you can stare at your feet as your ankles tug against the restraints. You could read a book if somebody would just prop it up on your chest. Or you could re-read the short inscription on that Jesus Lizard record that your brother had the band sign for you to cheer you up while you were in the hospital.

Or maybe you're not a sedentary person. Perhaps your idea of a good time is hanging off of a sheer rock face hundreds of feet in the air, belaying your partner as he picks his way through the next pitch of 5.14 cracks, running out of places to put any decent protection as a storm rolls into the valley. Don't strain your neck staring up at your partner's ass all day. Put on a pair of these prismatic "belay glasses" and look straight up while looking straight ahead. Or walk around the house looking at the ceiling as if it were the floor. Like you did when you were a kid.

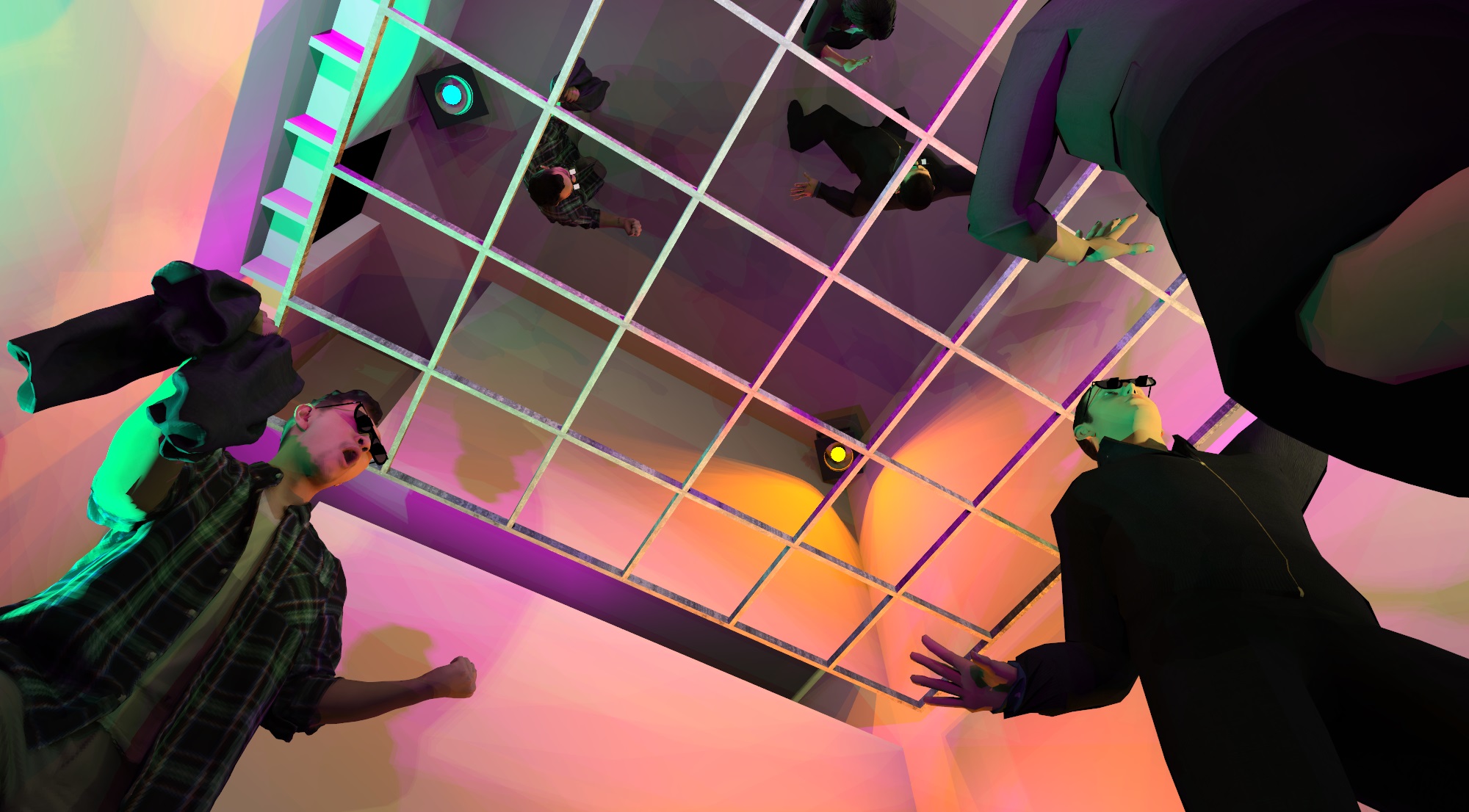

It is only because of Amazon and Facebook's intimate knowledge of my interests and shopping habits that I learned of the existence of belay glasses. I had the idea to create an installation like this years ago, but the glasses part of it just seemed too fussy and complicated to bother with. I shelved the idea and thought there was no way that anyone was ever going to make a commercially available pair of glasses that looked straight up in the air, but here we are. And here I am, preparing to spend more than $1K on acrylic mirrors to cover the ceiling of a gallery so that people can walk around in goofy glasses, looking at the tops of their own heads. This may turn out to be a perfectly pedestrian experience, or it may be mind blowing. There's only one way to find out. We're going to have to do it.

And this is how my recent artistic practices have really come to excite me. I don't know what's going to happen. It might not work at all. Or it might just be kinda lame. Or it might be completely disorienting with people bumping into each other and falling down. Or it might be totally transcendent.

I spend a lot of time making mock-ups and renderings to help myself envision the way things are going to work, and those things do help, but there's really no way to tell how these environments are going to work until you experience them in person. What I have tried to focus on here is simplicity. Works such as this can have all sorts of after-the-fact meanings attached to them, issues of surveillance, voyeurism, mysticism, etc can be layered onto a work like this in an attempt to make some sort of larger statement. I've been guilty of plenty of those things in the past. This time I would just like to keep it simple: a stage onto which other dramas can be projected. A frame or vessel in which art can be created and enjoyed. Or we can just dance and attempt to transcend ourselves in the most primal of ways - through music, and movement, and trance.

I had one of those moments at Tempus two years ago when Prince died and Tracy held an impromptu dance party in his honor. I'm not a dancer. Can you tell that I'm self conscious? I can't get out of my own skin. But that night I did, for just a few brief moments as we drank and danced and mourned the loss of someone that had pulled back the curtain for us so many years ago.

So let's make this a dance floor, and have a dance party. And we'll let Tempus and Tracy program the play list, and we'll hope that it's heavy on the Prince because we know that it will be. And we will literally leave our bodies behind. We'll project ourselves up and out to look down and see ourselves dancing - as others would see us - and not our own flawed conception of others as people who are critical of us because we are critical of ourselves and the others that we imagine are products of our own self-critical imagination. Actual others. Others who really don't give a shit about us, but also they don't live in our skin and they can see the beauty of our herky-jerky old man dance, or the wild mania of the twirling girl, or the joy in that guy who just keeps jumping straight up and down. We'll be both ourselves in our dancing meat bags and we'll be everything else that is not us and our meat. Or we'll just be a bunch or dorks walking around in silly glasses. Whatever. It's worth a shot."